Courier-Journal and Louisville Times Photo by Billy Davis III

Courier-Journal and Louisville Times Photo

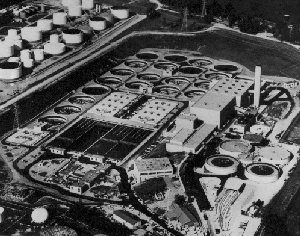

The Countywide Sewer Plan

The countywide sewer plan had been more or less stalled since 1964, mainly because of a lack of financing for the large treatment plants and their trunk sewer networks and lack of agreement about who would pay. The lack of action didn’t stop development, however: septic tanks continued to be built where the health department would allow them, and a multitude of small treatment systems were set up by developers where septic tanks were forbidden.

By mid-1972, there were about 350 small treatment plants in Jefferson County. During the preceding year, nearly half the 326 plants inspected by the health department had gotten "poor" ratings at least once.

Congress was taking action; the Clean Water Act of 1972 set a goal of making all of the nation’s waterways safe for fishing and swimming by 1983. To achieve this goal, aggressive new standards were set for sewage treatment plants: They would have to meet the "best practicable" technology by 1977 and the "best available" technology by 1983. They would also have to obtain permits to operate — which would include mandatory timetables for improvements — by mid-1975.

The new standards had expensive implications for the Morris Forman plant. It would need major improvements to meet them.

The new standards also brought two major additions to the MSD system: the Shively and St. Matthews sewer systems, which had been paying MSD to take their wastewater but had been operated separately.

And the new standards helped bring an end to MSD’s program of operating and maintaining small plants under contracts with their owners. In 1970, with contracts to operate 58 plants, MSD had stopped taking new customers; in 1972, MSD discontinued the program.

The new standards, coupled with the problems with small plants and septic tanks, stirred renewed interest in the countywide sewer plan. By early 1973, revisions were under way. The cost estimate: $654 million, more than twice the estimate of 1964. The new estimate included $309 million to separate Louisville’s storm and sanitary sewer systems. Under the clean-water program, the federal government would pay up to 75 percent of the cost.

The revised North County and West County plans were approved in 1974. Both plans provided that MSD would take over small treatment plants and collection systems as MSD’s trunk lines reached them.

Work was scheduled to begin first on the West County plan, including a new treatment plant to serve most of the area south of Louisville and Shively and west of Okolona. Work on the North County plan would come later.

By early 1976, the cost estimates had increased again: nearly $428 million for the West County and North County plans, according to official EPA figures. The EPA was pressuring MSD and local government officials to speed up the projects.

In June, 1977 Jefferson Fiscal Court approved a $23 million bond issue to help finance the West County plant and trunk sewers serving the areas near Fairdale and Okolona. On July 5th, MSD officially "initiated" the West County/Pond Creek plan.

And then the expansion plan came to a halt.

The Southwest Homeowners Association organized to fight sewer expansion, claiming septic tanks worked well and sewers weren’t needed. The organization threatened to go to court to force the EPA to prepare an environmental impact statement for the project. The EPA reviewed the situation and decided that an impact statement was needed.

Courier-Journal and Louisville Times Photo

In October, 1977 the MSD Board voted to delay further action on sewer expansion until the statement was completed.

The maneuvers continued into the early 1980s. The EPA’s impact statement, finally issued in 1982, said residential septic tanks worked well in the southwest, so sewers were not necessary except for businesses and industries. This finding conflicted with health department reports that many homes in the area took their water from wells, and septic tanks were polluting the groundwater. Tests showed that wells were polluted with bacteria and nitrates.

The result of the controversy: nine years after the 1974 plan was adopted, there had been little progress toward building the countywide sewer system.

MSD History continued - Drainage